This year began with a pandemic that seemed, at the outset, to be only located in Asia. By March, it became clear that COVID-19 was a pandemic. The world was not ready for it, but as infections spread, people did their best to tell uplifting stories: of people cheering health care professionals after a long shift at the hospitals; of people reading books to children; there are videos of people trying to make the best out of a frightening and difficult situation; and the world economy might even recover according to the president of the United States.

Then there were a series of events: a man was threatened at a park, and the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery and Breanna Taylor, and the murder of George Floyd. In a matter of weeks the riots began.

The death of George Floyd is the watershed moment of 2020. The event has demonstrated the urgent need for more social justice and racial equality, especially when law enforcers embody the very evil they swore to protect citizens against. The pandemic that had enraptured the worst of our imagination has taken a back seat. There are growing protests in cities worldwide, spurred by incidents of racial injustice and police brutality. Protesters have bellowed for radical change in the social order, highlighting their desire to recognize the rights of the historically disenfranchised. Yet the spirit of this revolution has brought with it the violent urges of individuals and groups willing to burn their own village, and risk diluting the message of reparations, justice and mercy.

What can teachers do in a time of crisis?

I struggled with this question as I watched events unfold. Often I reach for a book and I watch something online. From there, I drift from the awful reality in the news, distracted by the myriad of entertainment avenues online. This time, however, escapism has been difficult. The news about George Floyd everywhere, on the news and on social media. As a teacher I feel compelled to constantly assess the state of public life, in terms of discourse and civil action. I sympathize with the struggle for social justice, especially for those who want recognition, for people who feel they are not represented. Social media is replete with images of chaos, riots and deep political malaise. Well-meaning people are out in the streets risking their lives to stand up for a cause; to stop looters and rioters from destroying private property; and many of these people get hurt, and it seems that the best thing I can do, as language instructor in South Korea, is to remind my students that social justice is a relevant project for them as well.

The Social Justice Project - Classroom Speech and Poster Creation

My South Korean students have their own social and political issues. They have their own informed social and political opinions. My goal is not to preach about my own social justice interests. I am inspired by the recent protests, and I can talk about history of slavery and colonialism; I can present the recent cases of law enforcement and how it correlates with racist and discriminatory practices; I can certainly make the case to young people of the systemic injustice in America and how the latter is inseparable to socio-economic conditions. All of those options would amount to me lecturing, instead of asking my students of their own lived experiences that may very well include instances of injustice and inequality. Rather than discussing the riots in America and giving the topics to them, I decided that students should choose their own social issue.

Before undertaking this project, I thought of two questions: Will my students articulate their own concerns and fears of the relevant social problems that they have encountered? Will they express their own willingness to motivate others to improve and condition their social condition as citizens?

While thinking of these questions I realized that all I can do is help my students navigate the continuum of societal threats and problems, and lend a hand as they chart their own course of actions to bring their vision of social change into reality. It’s not up to me to create the ethos of their vision of a better world. I thought my chances would improve if I let my students decide for themselves, if I listen to what they have to say. If I desire for my students to recognize their capacity as civil agents, at best, I can only inspire them to act on behalf of a cause that they care about.

I broke down the task of the lesson in four parts. As a disclaimer, this lesson took more than a couple of meetings to complete.

1) Students will demonstrate how they understand a social issue

2) Students will write a campaign message in response to an issue of their choice

3) Students will create a campaign poster to promote their message

4) Students will compose and deliver a social issue speech

I wanted my students to speak about a social issue for at least a minute, and for them to demonstrate their understanding of the issue’s significance to others. As a secondary goal I thought it was important that my students create a final product, so that they can share it with their friends and family. A poster with a campaign message was a perfect vehicle for my students to spread their message of social change.

Did I have the racial tension in America in mind when preparing for this lesson? Did I want students to discuss George Floyd’s death, police brutality and social justice? Yes, of course.

Some of my students did talk about racism, and some of them spoke of other issues.

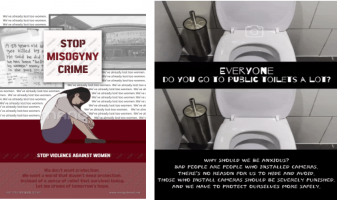

Here are a few posters.

The work that resonated in many of my classes were the ones that spoke to the issues closer to my students’ life experiences. Many of whom are young women who expressed their concern over recent incidents of misogyny, sexual harrasment and sexual violence in Korean public and digital spaces.

Some students talked of the violence against children; they referred to recent examples in South Korea in which children were victimized by their own parents and guardians. What I learned is that a singular issue of racism in America can be contextualized within a spectrum of injustices; for my students these issues are part of a larger framework of respect and dignity. Regardless of one’s identity, no human being wants to be a victim of violence. Everyone desires to be respected, to feel safe and protected.

I am very satisfied with the products that students submitted; I am happy that most of my students gave passionate speeches; and I am grateful that some of my students demonstrated a sincere commitment to human rights, justice, equality and social safety. There is still a question whether this lesson made any difference at all. Is awareness enough of these problems sufficient to precipitate greater changes and improvements? Can these posters and speeches really change the current tides of anger, frustration, and fear?

I raise these questions, since it is very likely that some of my students felt that this particular lesson was another assignment to be completed. Like the news cycle, the issues presented were heard at that time, but were replaced by more urgent concerns. And yet I believe that humanity has made progress, in small incremental steps; that in spite of all the suffering and setbacks, there is an evolution to social justice in the consciousness of human societies. The evolution of such progress cannot arise without a sense of commitment, responsibility and engagement towards our fellow beings. In times of crisis, the best teachers can do is remind our students of that moral duty, the infinite task of making our world a better place.

Author

Cyril Reyes is an assistant professor at Woosong University and a regular contributor to Korea TESOL's publicity efforts.