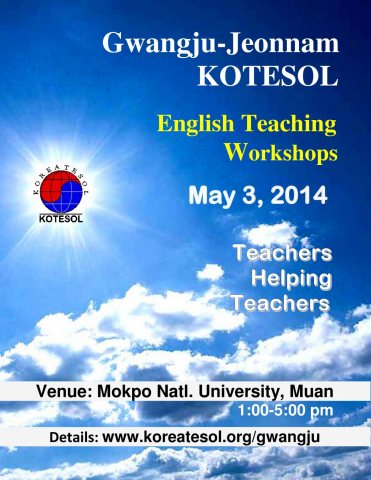

Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL May Outreach

Time: Saturday, May 3, 2014, 1:00–5:00 p.m.

Place: Mokpo National University (Muan, Jeonnam), Bldg. A10, Rm. 204

Directions to Venue: http://koreatesol.org/content/directions-mokpo-outreach

||||||| The program for this Outreach can be found as a PDF file at the bottom of this web page.

--- Schedule ---

1:00 pm: Sign-in and Meet-and-Greet

(Admission is free. Future membership is welcomed.)

1:15–1:30 pm: OPENING and INTRODUCTION of KOTESOL & the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter

1:30–2:15 pm: Opening Presentation

Second Language Learning and Teaching: Clarifying the Misconceptions

Dr. David E. Shaffer (Chosun University)

2:15–2:45 pm: Networking, Socializing, and Refreshments

2:45–3:30 pm: CONCURRENT PRESENTATIONS – SESSION 1

It’s All in the Balance: Creating the Ideal Lesson

Billie Kang (Taebong Elementary School; Master Teacher)

Looking at Teacher Talk Through The Johari Window

Jocelyn Wright (Mokpo National University)

3:45–4:30 pm: CONCURRENT PRESENTATIONS – SESSION 2

Stand Up and Read: Adding Movement and Excitement to Reading Activities

Henry Gerlits (Jeollanamdo Educational Training Institute)

Yielding the Floor: Tips and Techniques for Student-Centered Teaching

Lindsay Herron (Gwangju National University of Education)

4:40–5:00 pm: Drawing for Prizes and Closing

Presentation Abstracts and Presenter Biographical Sketches

Second Language Learning and Teaching: Clarifying the Misconceptions

By Dr. David Shaffer

Over the years, numerous beliefs about how languages are learned and how they should be taught have coalesced among laymen and foreign language teachers alike, often without very much theoretical foundation or research as a basis. The aim of this presentation is to challenge about fifteen such popular opinions and show how they are not supported or poorly supported by present second language acquisition research and theory. These opinions deal with first and second language acquisition beliefs, error correction, first language interference with language learning, pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar rules, structures, and interaction. The end goal is to produce a clearer perception of how second languages are learned and of current thinking on best practices for teaching them, making it possible for the teacher to make informed classroom instructional adjustments.

Everyone considers themselves to be an expert on language learning – after all, they have all managed to master at least one language and quite possibly more. As such, popular views on first and second language learning arise and many are accepted but the general public without question, and in many cases, without foundation. This presentation will take a look at over a dozen popular views on the language learning process first discussed by Lightbown and Spada (1993). Some of these popular views are slightly deviant from what research reveals; others have no research support.

The popular opinions to be challenged include: a) Languages are learned mainly through imitation. b) Parents usually correct young children’s grammatical errors. c) Highly intelligent people are good language learners. d) The best predictor of success in second language acquisition is motivation. e) The earlier a second language in introduced in school programs, the greater the likelihood of success in learning. f) Most of the mistakes that second language learners make are due to interference from their first language. g) It is essential for learners to be able to pronounce all the individual sounds in the second language. h) Once learners know roughly 1,000 words and the basic structure of the second language, they can easily participate in conversations with native speakers. i) Teachers should present grammatical rules one at a time, and learners should practice examples of each one before going on to another. j) Teachers should teach simple language structures before complex ones. k) Learners’ errors should be corrected as soon as they are made in order to prevent the formation of bad habits. l) Teachers should use materials that expose students only to language structures that they have already been taught. m) Teachers should respond to students’ errors by correctly rephrasing what they have said rather than by explicitly pointing out the error. n) Students learn what they are taught.

THE PRESENTER

David E. Shaffer (PhD Linguistics) is a long-time educator in Korea and long-time KOTESOL member. He is a professor at Chosun University, teaching English majors in the graduate and undergraduate programs. Dr. Shaffer is the author of several books on learning English as well as on Korean language, customs, and poetry. His present academic interests include professional development, and young learner and extensive reading research, as well as loanwords and effective teaching techniques. Within KOTESOL, Dr. Shaffer is presently Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter President, National Publications Committee Chair, and a member of several committees, including the International and National Conference Committees. He is the recipient of numerous KOTESOL awards and father of two KOTESOL members. Email: disin@chosun.ac.kr

__________________________________________

It's All in the Balance: Creating the Ideal Lesson

By Billie Kang

Some of us do too much; others do too little. Everything is about finding a good balance and this includes teaching, too. Having demonstrated classes of my own and observed classes of other teachers for the past two years as a master teacher have given me great opportunities to reflect on how to find a good balance between activities to make a lesson more successful. The aim of this presentation is to demonstrate a “routinized class” model with generic warm-up and wrap-up activities that would help young children to perform well in the development stage of the lesson. Effectiveness and efficiency will also be talked about to find or to design good games and activities. Attendees will have the opportunity to practice some of the games and activities in pairs and small groups.

THE PRESENTER

Billie Kang has worked with young children since she started her teaching career at elementary school in 1997. Her undergraduate major is in elementary pedagogy from Gwangju National University of Education and her M.Ed. in TESOL from SUNY Buffalo (USA) was completed in 2003. She has given lectures at various workshops and training courses on various topics for both Korean and non-Korean teachers. She is currently teaching English at Taebong Elementary School in Gwangju as a master teacher. Outside of the classroom, she has just recently taken up bike riding and plans to enjoy it more this year.

What is a “master teacher”? Master teachers are a select group of teachers with more than 15 years of teaching experience and pass a rigorous screening program by their office of education. The program was instituted in 2012, and the main responsibilities that master teachers have are mentoring through class demonstrations and consultation. Currently, there are 22 elementary and 31 secondary school master teachers in Gwangju.

______________________________________________

Looking at Teacher Talk Through The Johari Window

By Jocelyn Wright

If you monitor your teacher talk or have the chance to observe other teachers around you and attend carefully to their speech, you might be surprised at what you hear! Even experienced teachers occasionally produce what is commonly referred to as “semantic noise” (Shannon & Weaver, 1949) in the field of communications. This kind of noise, which is most likely to be problematic if working with low-level learners, is essentially language that interferes with listener comprehension in an exchange.

Yet, to maximize language learning in communicative language classrooms, one key teaching goal should be to provide students with comprehensible input (Krashen, 1982). At the same time, another aim is to place learners at the center of activity and to get them producing the target language (Swain, 1985). To promote authentic language learning opportunities given often limited contact hours, teachers are, therefore, encouraged to focus both on the quality and quantity of their teacher talk.

Researchers have long argued that much classroom interaction, characterized by numerous pedagogical functions (e.g., explaining, commanding, questioning, modeling, giving feedback, etc.), does not genuinely reflect real-world communication. As such, improving on these aspects is essential.

In this workshop, we will focus on one common function: giving instructions. After doing a practice exercise, we will discuss what verbal and non-verbal characteristics contribute to their effectiveness. Then, with the aid of a peer observer, we will reflect on our output. To do this, we will primarily use a model called The Johari Window (Luft, 1969). This exploratory tool, originally designed for the development of interpersonal communication skills, lends itself well to collaborative reflective practice. A follow-up self-transcription proof-listening activity (adapted from Lynch, 2001) will also be proposed.

This three-step routine, consisting of simulation, interactive paired feedback, and more careful analysis is specifically intended to contribute to a greater awareness of teacher talk and provide new insights that will lead to improved classroom performance.

More generally, though, it is hoped that these noticing and reflection techniques will be applied to ongoing professional development efforts and, possibly, future action research projects.

THE PRESENTER

Jocelyn Wright works in the Department of English Language and Literature at Mokpo National University. She has an honor’s degree in linguistics, a master’s degree in education, and is also CELTA certified. Besides Korea, she has taught in Canada, the Dominican Republic, and France. Jocelyn actively servesKOTESOL as both a Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter officer and as a facilitator of the local Reflective Practice Special Interest Group (RP-SIG). These activities are in keeping with her keen interest in the areas of professional development and teacher training. Email: jocelynmnu@yahoo.com

REFERENCES

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Oxford, England: Pergamon Press.

Luft, J. (1969). Of human interaction. Palo Alto, CA: National Press Books.

Lynch, T. (2001). Seeing what they meant: Transcribing as a route to noticing. ELT Journal, 55(2), 124-132.

Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and output in its development. In S. Gass & C. Madden (Eds.), Input in second language acquisition (pp. 235-253). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

___________________________________________________________________

Stand Up and Read: Adding Movement and Excitement to Reading Activities

By Henry Gerlits

Reading? In an elementary English classroom? With all the energy that elementary school students have, sometimes it’s difficult to ask them to sit down and do reading activities. So why not have them stand up and read instead? This workshop will explore different ways to add movement and excitement to reading activities, while preserving their educational value.

We’ll begin with warm-ups – some traditional “pre-reading” activities including a preview of vocabulary and some others adapted from theater ice-breakers. We'll start with a board race, with participants lined up in teams at a whiteboard, activating background knowledge of vocabulary and content as the presenter directs them with some speed-writing to raise the energy level for the activities ahead. Next up is a modified charades game, ideal for refreshing knowledge (or providing a first introduction for lower level students) of verbs in the lesson’s target language.

From there we’ll move toward engaging “during-reading” variations that will keep your students hopping in their seats – or maybe even jumping out of them! For the first reading, I’ll ask the participants to focus on a single question while they listen to the story read aloud. The second time, they’ll be encouraged to create their own mimes. By injecting gestures and emotions into reading, we’ll keep focused on the English meaning of the readings, and hopefully help build memorable connections to the text. We’ll end up with some effective ways to improve comprehension and vocabulary retention while also keeping the class engaging for young minds.

In addition, this workshop will explore the concept of Reader’s Theater – reading activities with a focus on the emotion and intonation of play dialogue. Before we start Reader's Theater, we’ll do a couple of warm-up games adapted from a high school theater department. Designed to use a little bit of English and get a lot of laughs, these games will help students ease up before a performance by inviting a bit of the absurd into the classroom.

During the Reader’s Theater portion of the presentation, participants will experience a little of the pressure and thrill of performance. By adapting these activities into your own classroom, your young learners will have the opportunity to forget that they’re “learning English” and can focus on the plot and comedy of an acted-out story. With props and maybe even some marks and blocking, we’ll discover a new dimension of reading and storytelling. And of course – theater is perfect for getting everyone out of their seats and moving!

From warm-ups to dynamic readings to active review, these activities will help your young learners grow into young readers. I’m hoping that you’ll join me in this very active workshop. Watch out, I’ll make you all stand up as well!

THE PRESENTER

Henry Gerlits first started teaching in 2005, arriving with the Fulbright program on Jeju Island and working at a middle school for a year. Since then he’s taught at Cheju National University, Yokohama College of Commerce, an adult education center in his hometown of Boston, and for two years at Gwangju University, before starting at the Jeolla-namdo Educational Training Institute (JETI) in Damyang. Henry received his Master’s degree in Applied Linguistics from the University of Massachusetts Boston and is always looking for new ways to improve his teaching practice. He’s just started his second year of teaching at JETI and is loving it – he gets to discuss linguistics, etymology, and teaching methodology all day! His other interests include hiking, cooking, yoga, strategy gaming, and traveling. Email: henry.gerlits@gmail.com

______________________________________________________________

Yielding the Floor: Tips and Techniques for Student-Centered Teaching

By Lindsay Herron

Paulo Freire once lamented that in the traditional “banking” model of education, the teacher is perceived as the sole possessor of knowledge in the classroom. His job is “to ‘fill’ the students with the contents of his narration” (Freire, 1993), as if they were empty vessels. This isn’t true, however; students come to the class filled with their own experiences, background knowledge, interests, abilities, and beliefs.

Student-centered teaching rejects the traditional model of education in favor of an approach that respects and integrates the knowledge students bring to the classroom. It shifts the teacher from the center of the classroom to the periphery, making him less a “sage on the stage” than a “guide by the side.” Some teachers believe that a student-centered approach can’t be instituted in Korea; that because of the demands of the national curriculum and washback from the university entrance exam, a traditional, teacher-centered class is the most efficient way to dispense knowledge. In this workshop, however, we’ll discuss simple ways to make classes student-centered—without sacrificing exam preparations.

David Paul’s (2004) model of child-centered learning offers an excellent starting place for this. His model includes five steps: notice, want, challenge/take risks, play/experiment, succeed, and link. Teachers, he says, should give students space to notice new words or patterns, and give them a reason to want to know the meaning. After students’ interest is piqued, they can make guesses about the pattern, practice using it, learn from their mistakes, and finally begin to use the pattern creatively in myriad situations. The pattern ultimately finds a place in their mental model of English.

Teachers can use this model as a framework for making lessons more student-centered. A few simple adjustments to one’s teaching approach can make a world of difference!

THE PRESENTER

Lindsay Herron has been a visiting professor at Gwangju Natl. University of Education in Gwangju since 2008. Prior to that, she taught English on a Fulbright grant at Seogwipo High School in Jeju-do. She has a master’s degree in Cinema Studies from New York Univ., bachelor’s degrees in English and Psychology from Swarthmore College, a CELTA, and the CELTA YL-Extension. She is currently working on a master’s in Literacy, Culture, and Language Ed. from Indiana University-Bloomington. At the National level, Lindsay is currently Chair of the Membership Committee and has served on the 2012 and 2013 International Conference Committees.

||||||| The program for this Outreach can be found as a PDF file at the bottom of this web page.

||||||| The poster for the Outreach is there, too.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 549.49 KB | |

| 112.48 KB |